The Project Gutenberg eBook of Humpback Whales in Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Humpback Whales in Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska

Author: United States. Marine Mammal Commission

Release date: August 15, 2011 [eBook #37101]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Tom Cosmas, Joseph Cooper and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HUMPBACK WHALES IN GLACIER BAY NATIONAL MONUMENT, ALASKA ***

[Cover]

National Technical Information Service

PB80-141559

HUMPBACK WHALES

IN GLACIER BAY

NATIONAL MONUMENT, ALASKA

MARINE MAMMAL COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, D.C.

FEBRUARY 1980

[Pg ii]

QL 737 .C424 H86x

Humpback whales in Glacier

Bay National Monument, Alaska

[Pg iii]

Report No. MMC-79/01

HUMPBACK WHALES IN GLACIER BAY NATIONAL MONUMENT, ALASKA

Marine Mammal Commission

1625 I Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Published February 1980

Prepared by

U.S. Marine Mammal Commission

1625 I Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

[Pg iv]

NOTICE

THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED FROM THE BEST COPY FURNISHED US BY

THE SPONSORING AGENCY. ALTHOUGH IT IS RECOGNIZED THAT CERTAIN PORTIONS

ARE ILLEGIBLE, IT IS BEING RELEASED IN THE INTEREST OF MAKING AVAILABLE

AS MUCH INFORMATION AS POSSIBLE.

[Pg v]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This Form may be reproduced.

[Pg vi]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |||

| PREFACE | 1 | ||

| INTRODUCTION | 2 | ||

| BACKGROUND | 2 | ||

| Distribution and Abundance of Humpback Whales in the North Pacific | 2 | ||

| Glacier Bay | 3 | ||

| Humpback Whales in Glacier Bay | 7 | ||

| Human Use of Glacier Bay | 10 | ||

| POSSIBLE CAUSE-EFFECT RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN HUMAN USE OF GLACIER BAY AND THE DISPLACEMENT OF HUMPBACK WHALES FROM THE BAY | 13 | ||

| ADEQUACY OF EXISTING DATA | 21 | ||

| MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH ACTIVITIES TAKEN OR UNDER CONSIDERATION | 21 | ||

| ALTERNATIVE MANAGEMENT ACTIONS | 23 | ||

| IDENTIFYING AND SELECTING THE MOST APPROPRIATE RESEARCH/MANAGEMENT STRATEGY | 24 | ||

| AGENCY RESPONSIBILITIES AND NEED FOR COOPERATION AND COORDINATION | 26 | ||

| SUMMARY | 27 | ||

| REFERENCES | 29 | ||

| APPENDICES | |||

[Pg vii]

LIST OF TABLES

| Page | |||

| 1. | Relative abundance and distribution of identified humpback whales in southeast Alaskan waters 1967-79 | 8 | |

| 2. | Number of humpback whales (individual census) entering Glacier Bay during "influxes" | 9 | |

| 3. | Age composition of humpback whales per year in Glacier Bay | 9 | |

| 4. | Juraszs' description of "stress behavior" | 11 | |

| 5. | Juraszs' vessel/aircraft classes | 12 | |

| 6. | Number of visitors and vessels to Glacier Bay National Monument | 14 | |

| 7. | Number of vessel sightings per month in each class as seen from the Juraszs' R/V GINJUR | 15 | |

| 8. | Average vessel sightings per day in each class as seen from the Juraszs' R/V GINJUR | 16 | |

LIST OF FIGURES

| Page | |||

| 1. | Southeast Alaska, Alexander Archipelago | 4 | |

| 2. | Glacier Bay, Alaska | 5 | |

| 3. | Glacier Bay, Alaska showing former positions of termini 1760-1966 | 6 | |

| 4. | Commercial fishing vessel visits to Glacier Bay | 17 | |

| 5. | Commercial fishing activity Glacier Bay | 18 | |

| 6. | Fishing charter boats and private boat visits to Glacier Bay 1970-1977 | 19 | |

[Pg 1]

PREFACE

In 1976, the National Park Service initiated a study to

determine whether increased boat traffic or boating activities

were having an adverse impact on humpback whales inhabiting

Glacier Bay National Monument during the summer months. In 1978,

the whales entered the Bay as usual, but left sooner than expected.

The scientists conducting the whale studies believed that the

early departure of the whales was precipitated by increased boat

traffic in the Bay and, in 1979, the Park Service, in consultation

with the cruise ship industry, developed and implemented operational

guidelines for vessel course and speed in designated areas,

where it was felt that vessel interactions with incoming whales

could cause the most disturbance.

Researchers spent many hours looking for whales in the Bay

during the early part of the 1979 summer season, but few whales

were seen. Several interactions between vessels and those whales

present in the Bay were observed and, on one occasion, a whale

known to have had an interaction with a vessel left the Bay.

Monument personnel discussed the problem with the area office of

the National Park Service. A number of options, including

emergency closure of the Bay were considered. It was decided to

provide funds for a more thorough analysis of the available

information on whale/vessel interactions, and to consult with

the National Marine Fisheries Service pursuant to Section 7 of

the Endangered Species Act.

The NMFS was advised of the situation and, on 10 August 1979,

NPS and NMFS representatives met in Seattle, Washington to review

available information concerning the nature and possible causes

of the departure of whales from the Bay. Another meeting was

held in late August to discuss the problem with members of the

cruise ship industry. It was agreed that additional research

was needed to better define the nature and possible causes of the

problem and that a meeting should be held to discuss possible

research approaches with other professionals in the marine mammal

field. These decisions led to the meeting described in this

report.

Subsequent to the meeting reported here, the National Marine

Fisheries Service in a letter dated December 3, 1979, responded

to the National Park Service's request for a Section 7 consultation.

A copy of the NMFS's response is provided in Appendix D

of this report.

[Pg 2]

INTRODUCTION

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) inhabit the

inland waters of southeast Alaska, including Glacier Bay

during the summer months (June-August). In the years from

1967 through 1977, 20 to 25 individually recognizable whales

were observed feeding in Glacier Bay. In 1978, the whales

entered the bay but left earlier than expected. In 1979,

only a few humpbacks entered Glacier Bay. The limited information

available suggests that increased human activity in the

Bay may have been responsible, at least in part, for the

observed shift in distribution. Increased human use of

coastal waters is not limited to Glacier Bay and the movement

of humpbacks from Glacier Bay to areas outside the Bay may be

symptomatic of a larger problem.

The purposes of this meeting were: (1) to review available

information concerning the nature and possible causes of the

movement of whales from Glacier Bay; (2) to review present

and planned research and management actions relating to

humpback whales in Glacier Bay and southeast Alaska; and (3) to

identify additional research or management actions that may be

necessary to conserve and protect the North Pacific population(s)

of humpback whales.

The meeting was held on the 12th and 13th of October 1979,

at the College of Fisheries, University of Washington, Seattle.

The meeting agenda is included as Appendix A. Individuals who

made formal presentations at the meeting are identified on the

agenda. A list of the meeting attendees, their organizations,

addresses, and telephone numbers are listed in

Appendix B.

BACKGROUND

in the North Pacific[1]

Humpback whales are seasonal migrants found in all of the

world's oceans. In the North Pacific, humpback whales winter

in tropical regions over the shallow coastal shelfs associated

with the Hawaiian Islands, Baja California, central Mexico,

the Ryukyu Islands, Bonin Islands, and Mariana Islands. They

summer in cold temperate regions, also over shallow coastal

shelfs, from Point Conception, California, north through

Alaska, west through the Aleutians, and south to Honshu

Island, Japan. Calving and probably breeding occur on the

wintering grounds. Feeding is believed to occur primarily in

the summering grounds.

[Pg 3]

In Alaska, humpback whales are known to inhabit Prince

William Sound, the waters of the Alexander Archipelago, and

the waters adjacent to Kodiak Island and the Aleutians. Some

whales may also overwinter in the northern summering areas.

The distribution, movements, abundance, and habitat

requirements of humpback whales are not well known. Based

upon Japanese catch statistics, the pre-exploitation population

of humpback whales in the North Pacific is estimated

to have been approximately 15,000. Much of the exploitation

of humpback whales occurred in the twentieth century,

especially during the early 1960's. A small number of whaling

stations established in southeast Alaska took humpbacks

between 1907 and 1922. In 1966, the International Whaling

Commission imposed a worldwide ban on the taking of humpback

whales.

The present population of humpback whales in the North

Pacific is estimated to be about 1,000 animals. The number

occurring in tropical waters during the winter is thought to

be about 600-700 in Hawaii, 200-300 in Mexican waters, and a

"few whales" in the western North Pacific. More than 100 individual

whales have been identified in the inland waters of southeast

Alaska during the summer. Tagging experiments with Discovery

Marks indicate movement between the Aleutian Islands and the

Western North Pacific; recent photo-identification studies have

shown movement from Southeast Alaska to both the Hawaiian Islands

and Baja (and southern coastal) Mexico. There is no substantive

evidence to indicate whether the number of humpback whales, on

either summer or winter grounds, in the North Pacific is

increasing or decreasing.

[1] This summary is based on information provided at the meeting

by Drs. Michael Tillman and Louis Herman.

[Pg 4]

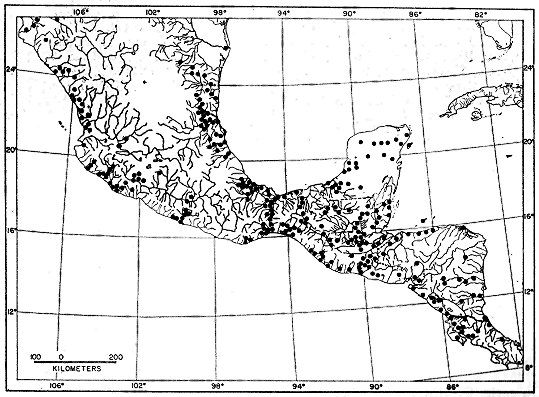

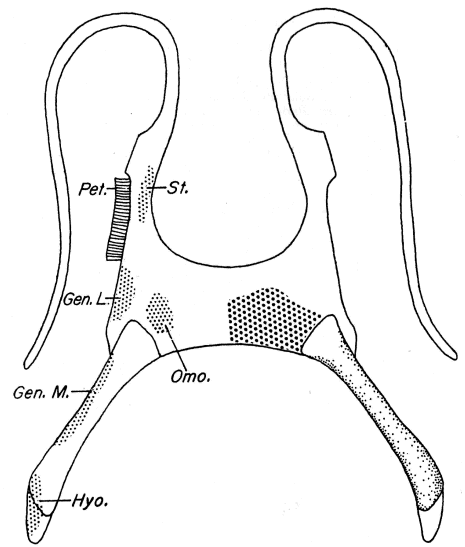

FIGURE 1. Map showing location of Glacier Bay, Lynn Canal and Fredrick Hole in Southeast Alaska Alexander Archipelago (from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

[Pg 5]

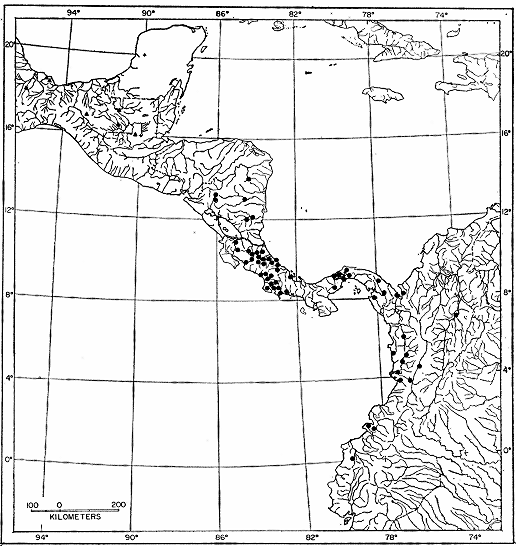

FIGURE 2. Soundings in Fathoms (NOS Chart 17300)

Click on map for larger size.

[Pg 6]

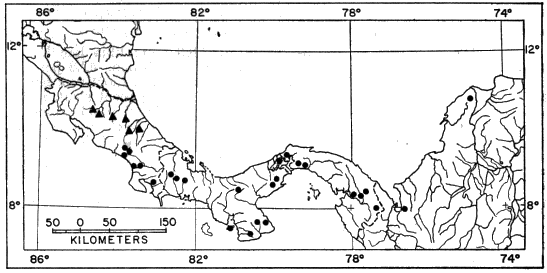

FIGURE 3. GLACIER BAY, ALASKA SHOWING FORMER POSITIONS OF TERMINI 1760-1966

(from Hale and Wright, 1979)

Click on map for larger size.

Glacier Bay is located near the north end of the

Alexander Archipelago (Figures 1 and 2). The Bay opens into

Cross Sound and Icy Strait of the Inside Passage of southeast

Alaska. When Vancouver discovered the area in 1780, glacial

ice filled the Bay to its mouth (Figure 3). In 1891, when

the Bay was first mapped, Muir Inlet was still filled with

ice. Today the ice has retreated up the right (Muir Inlet) arm

of the "Y" shaped Bay to tide-water levels. Recently, glacial

ice has started to readvance in the upper reaches of the

west inlets of the Bay.

[Pg 7]

The Bay is defined by shallow sills at its entrance

and the entrance to Muir Inlet. Constricted channels in

which tidal currents are locally strong occur between sediment

covered shores in the lower end of the Bay and the east (Muir)

inlet. Deep, unconstricted bedrock channels and basins with

weak currents occur in mid-Bay and the west inlet. These

features and the configuration of the bay produce a tidal

range of 8 meters. There is reduced mixing of waters

within the Bay and between the Bay and Cross Sound/Icy Strait.

Annual precipitation up to 4 meters, coupled with glacial

melt water, create a surface layer and flow of cold fresh

water out of the Bay. Strong flood tides push sea water into

the Bay over the sills. The dynamics of the flow may effect

the behavior and timing of the movement of whales into (on

flood tides) and out of (on ebb tides) the Bay (see below).

During the winter, an increase in sea water flow and mixing

occur. Increased nutrient levels and sunlight in spring/summer

provide sufficient nutrients and energy for phytoplankton "blooms"

to occur. In turn, zooplankters appear, especially in the

open areas of mid and lower Bay (e.g., euphausiids) and along

glacial ice faces (e.g., mysids and amphipods). By autumn,

plankton concentrations diminish as light and nutrient levels

decrease. Small schooling fish, (e.g., capelin, Mallotus

villosus and Pacific sand lance, Ammodytes hexapterus), feed on

the plankton when it becomes available. Both fish and plankton are

consumed by humpback whales as well as by other predators. Other

marine mammal species reported in the Bay are harbor seals

(Phoca vitulina), harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena), killer

whales (Orcinus orca), and minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata).

[2] This summary is based on information provided at the

meeting by Mr. Gregory Streveler.

The distribution in and use of Glacier Bay by humpback

whales was not well known until Charles and Virginia Jurasz

began observations in 1973. Prior to this, only personal

recollections of Park Service employees of the occurrence of

humpback whales in the 1950's and the 1960's exist. In

1967, 60 identifiable humpback whales were observed in three

southeast Alaskan areas, i.e., Lynn Canal, Frederick Sound,

and Glacier Bay. The number of identifiable whales remained

relatively constant until 1974 in Lynn Canal, and 1978

(July 17) in Glacier Bay (Tables 1-3). In the respective areas,

the number of identified whales decreased from 15 and 19 to

1 and 3, respectively. Concurrently, the number of identified

whales sighted in Frederick Sound increased.

[Pg 8]

TABLE 1. Relative abundance and distribution of identified humpback

whales in southeast Alaskan waters 1967-79[a]

| Year | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 |

| Glacier Bay | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 19/3[b] | 3 |

| Lynn Canal | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1/5 | 5 |

| Frederick Sound | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40/50 | 80 |

| Total | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 65 | 61 | 68 | 68 | 68 | 60/58 | 88 |

[a] Specific dates of censuses, sighting techniques and sighting effort not given.

Based on a table presented by the Juraszs at the meeting.

[b] First number signifies number originally counted at beginning of

season/second number after decrease in number of whales in Glacier

Bay and increase in other areas. The identified whales that left Glacier

Bay are not necessarily the same individuals that produced the increased

numbers in Lynn Canal and Frederick Sound later.

[Pg 9]

TABLE 2. Number of humpback whales (individual census) entering Glacier Bay during "influxes". (modified from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

| Year | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 |

| First Influx | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Second Influx | 11 | 17 | 16 |

| Seasonal Maximum | 20 | 24 | 23 |

TABLE 3. Age composition of humpback whales per year in Glacier Bay (modified from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

| YEAR | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 |

| NO. OF CALVES | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| NO. OF IDENTIFIED ADULTS | 14 | 14 | 18 |

| NO. OF JUVENILES | 6 | 1 | |

| TOTAL NO. OF ADULTS | 19 | 19 | 18 |

[Pg 10]

Identifiable humpback whales were sighted in Glacier Bay

each year, 1976-1977, for a six to twelve week period. In 1978,

all but three whales departed the Bay after 16 days. In the

summers of 1976-1978 two influxes of whales occurred (Table 2).

The Juraszs' define an influx of whales as those whales that enter

and remain in the Bay for a minimum of three weeks. The

second influx arrived 7-14 days after extreme low tides

occurred in late June-early July and presumably moved into the

Bay on flood tides. In 1979, a single influx comprised of 3 whales

entered the Bay. The age composition of identified whales

using Glacier Bay was categorized by the Juraszs' for 1976-1978

(Table 3).

During the period spent in the Bay, humpback whales have

been observed to feed on capelin, euphausiids (Euphausia pacifica),

and pandalid shrimp (Pandulus borealis). There appear to be

three generalized feeding relationships: 1) early-season feeding

on shrimp in the upper Bay; 2) mid-season feeding by concentrations

of whales on capelin in the lower Bay; and 3) late-season feeding

(around August 5) by concentrations of whales on euphausiids in

mid-Bay.

Behaviorally, humpback whales appear to lunge up through

concentrated schools of prey during mid-season and use

"bubble-netting" as a means of concentrating less dense

and/or numerically fewer prey earlier and later in the

season. In other areas of southeast Alaska, humpbacks

are reported to also feed on herring (Clupea harengus pallasi),

shrimp, and possibly other small schooling (swarming) prey.

The Juraszs' believe that humpbacks establish feeding

territories in the Bay, and have described eight "stress

behaviors" associated with violations of those territories

(Table 4). The data collected by the Juraszs are extensive

(including human use of Glacier Bay) but have not yet been

completely analyzed.

[3] This summary is based on information provided at the meeting

by Charles and Virginia Jurasz.

John Muir popularized Glacier Bay, leading to tourist

activity into the early 1900's, when loose ice resulting from

earthquake activity prevented cruise vessels from operating

within the Bay. Glacier Bay was designated a National

Monument February 26, 1925, the area being added to April 18, 1939.

Vessel and tourist numbers remained low until the late

1960's-early 1970's. Close to 100 percent of the visitors to

the Bay use vessels, either entering the Bay aboard them or

making use of them to tour the Bay after arriving by aircraft.

The Juraszs' developed a classification scheme for vessels

and aircraft based upon activities of the craft in the Bay,

their size, hull design, and engine characteristics (Table 5).

[Pg 11]

TABLE 4. Juraszs' description of "stress behavior" (Progressing from the least "stressful" to the most "stressful") (modified from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979.)

| Mode | Description |

| Vocalization | Bellowing or trumpeting noise produced by a whale and heard above and below the water. Emanates from the blowhole at the time of the expiration. |

| Bubbling | Premature or underwater release of breath in a straight line or as a single "belch" allowing the whale to avoid having a visible blow. Bubbles released usually 2-3 m below the water's surface. |

| Finning | Flipper slapping; the striking of the water's surface with the pectoral fins. |

| Tail Lobbing | Raising the flukes well out of the water and crashing or slapping them back flat against the water's surface producing a loud sound. |

| Tail Rake | A subset of the tail lobbing is the rake in which the flukes are raked laterally across the water's surface. |

| Half or Full Bodied Breach | A leap from the water in which a portion of the whale's body emerges from the water only to reenter with a large splash. |

| Avoidance | The temporary leaving of an area or a change in the direction of travel. |

| Abandonment | Leaving an area prematurely and not being seen again for at least one season in that area. |

[Pg 12]

TABLE 5. Juraszs' vessel/aircraft classes (after Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

| Class 1 | Touring Vessel Over 10k Tons |

| Class 2 | Touring Vessel 5k-10k tons |

| Class 3 | Commercial Fishing/Crabbing |

| Class 4 | Charter & Pleasure |

| Class 5 | Cabined High RPM Outdrive Units |

| Class 6 | Sailboat Using Aux. Power |

| Class 7 | Utility Craft, Outboard Engine |

| Class 8 | Kayak, Sailboat (no engines) |

| Class 9 | Aircraft, Fixed |

| Class 10 | Aircraft, Rotor |

| Class 11 | Aircraft, Jet |

| Class 12 | Hydrofoil |

| Class 13 | Another Humpback |

| Class 14 | Killer whales |

| Class 15 | Minke Whales |

| Class 16 | R/V GINJUR (Juraszs' research vessel) |

| Class 17 | Wake Only |

[Pg 13]

The increase in visitors and vessels to Glacier Bay is presented

in Tables 6-8. (Data included in Table 6 cannot be compared

to data presented in Table 7 because of difference in methods

of data collection, sample area, time, effort, etc.)

Commercial fishing vessel activity in the Bay was probably

low until the 1970's. Since 1972 (it is not known whether

data are available prior to 1972) commercial fishing vessel

visits have fluctuated (Figure 4), but fishing activity has

been greatest during the summer months (Figure 5). Sport

fishing visits have increased during the same time period

(Figure 6).

[4] This summary is based on information presented at the

meeting by Mr. John Chapman and Charles and Virginia Jurasz.

POSSIBLE CAUSE-EFFECT RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN HUMAN USE OF GLACIER BAY AND THE DISPLACEMENT

OF HUMPBACK WHALES FROM THE BAY[5]

The meeting participants agreed that the observed decrease

in the number of whales in Lynn Canal in 1974 and

Glacier Bay in 1978 may be attributable to a number or combination

of factors. Available evidence suggests human activity was

at least one of the causes, or served to trigger otherwise

"natural events". In Lynn Canal, humpback whales were known

to feed on herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). In 1974, the

year a herring fishery began, the number of humpback whales

dropped to one (Table 1). Between 1974 and 1978 fishing

continued. There was no fishing in 1979.

Use of the Canal by Class 5 vessels (cabin cruisers with

high RPM outdrive units) increased by 15-20 percent each year

after 1970 (Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979, p. 85). Three humpback

whales were seen in Lynn Canal during the 1975-1977 seasons,

the number increasing to five in 1978-1979. The relationship

between vessel activity, fishing effort, fish take, fish

abundance, and the presence and activity of whales in Lynn

Canal does not appear to be documented.

In Glacier Bay, increased vessel traffic may be one of

the factors responsible for the movement of humpback whales

from the Bay in 1978 and 1979. The Juraszs' data, while not

evaluated fully, suggest that there has been a general increase

in avoidance by humpback whales of Class 1 through 5 vessels

over the three year period, 1976-1978.

[Pg 14]

TABLE 6. Number of visitors and vessels to Glacier Bay National Monument.[a]

| Year | Visitation | Increase | Private Vessels Juraszs' Classes 1-2 | Cruise Ships (incomplete count) Juraszs' Classes 4-8 | |

| 1965 | 1,800 | ||||

| 1969 | 16,000 | 789% over 1965 | 450 | ||

| 1970 | 29,700 | 86% over 1969 | |||

| 1972 | 33 | ||||

| 1978 | 109,500 | 269% over 1970 584% over 1969 | 123 | 1800 | |

| 1979 | 123 | ||||

[a] Based on a table and information provided at the meeting by

Mr. John Chapman, National Park Service. (Modified by adding

Juraszs' classes of vessels.)

[Pg 15]

TABLE 7. Number of vessel sightings per month in each class as seen

from the Juraszs' R/V GINJUR. (from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

| 1977 | 1978 | ||||||||

| Vessel Class | June | July | August | TOTAL | June | July | August | TOTAL | |

| 1 | 20 | 22 | 11 | 53 | 17 | 25 | 8 | 50 | |

| 3 | 67 | 18 | 6 | 91 | 62 | 31 | 64 | 157 | |

| 4 | 37 | 42 | 30 | 109 | 29 | 125 | 64 | 218 | |

| 5 | 38 | 45 | 17 | 100 | 27 | 61 | 24 | 112 | |

| 6 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 29 | 19 | 48 | |

| 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 17 | |

| 8 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 16 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 17 | |

| 12 | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

[Pg 16]

TABLE 8. Average vessel sightings per day in each class as seen from

the Juraszs' R/V GINJUR. (Modified from Jurasz and Jurasz, 1979)

| Vessel Class | 1977 | 1978 | Percent Decrease | Percent Increase |

| 1 | 3.90 | 3.20 | 18% | |

| 3 | 5.74 | 13.47 | 135% | |

| 4 | 8.38 | 16.87 | 101% | |

| 5 | 6.93 | 8.19 | 18% | |

| 6 | 1.11 | 3.99 | 259% | |

| 7 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 14% | |

| 8 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 5% | |

[Pg 17]

Figure 4. COMMERCIAL FISHING VESSEL VISITS TO GLACIER BAY (from Hale and Wright, 1979)

[Pg 18]

Figure 5. COMMERCIAL FISHING ACTIVITY GLACIER BAY (from Hale and Wright, 1979)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[Pg 19]

FIGURE 6. FISHING CHARTER BOATS AND PRIVATE BOAT VISITS TO GLACIER BAY 1970-1977 (from Hale and Wright, 1979)

Natural changes in the environment and/or in the behavior

of whales have occurred concurrently with increased human/vessel

activity in Glacier Bay. Such natural changes include

spatial and temporal trends or cycles in the physical

(temperature, tides, currents, turbidity, etc.), chemical

[Pg 20]

(salinity, dissolved gases, inorganic/organic substances—nutrients,

etc.) or biological (primary productivity,

zooplankton, nekton, benthic species, predators, etc.)

properties or characteristics of the waters within and outside

the Bay. Temporal and/or spatial differences in relative

abundance of three different prey species within and outside

the Bay may have occurred and been responsible, at least in

part, for the movement of humpbacks from Glacier Bay.

At this time, data are inadequate to relate the movement of

humpback whales from Glacier Bay in 1978 and 1979 to physical,

chemical, or biological factors. Meeting participants felt

that physical and chemical factors were unlikely to have

changed sufficiently between 1976 and 1978 to affect humpback

whales, while biological factors, perhaps as a result of

physio-chemical changes, could have changed sufficiently to

have caused or contributed to the movement.

Human activity may have caused changes in the physical,

chemical, or biological environment, effecting humpbacks

directly or indirectly. Human and vessel activities

may have occurred such that the space (vertical and/or

horizontal) available to whales for normal activities was

less than that necessary (below some threshold level or

value). "Too many" vessels may have transited an area and/or

approached whales "too closely" for "too long" a period of

time, producing visual, acoustic, tactile, chemical, or

other as yet unknown stimuli at levels or values (magnitude,

intensity, duration, frequency, interval, etc.) greater

than the whales would tolerate. The physical-acoustic

environment may have changed as a result of sounds produced

by vessels. Vessel sounds may be modified, amplified,

intensified, etc., as a result of the geological/topographical

features of Glacier Bay (and perhaps Lynn Canal as well). Direct

interference with the whales' own sounds may have occurred or

"environmental" sound levels may have exceeded certain thresholds.

Basic data on the acoustic properties and characteristics of

Glacier Bay with and in the absence of vessels are lacking.

Changes in water quality may have occurred through

pollution. Data are insufficient to document the past or

present levels of pollution, but they were thought by meeting

participants to be relatively low.

Changes in the biological environment induced by human

activity may be contributory to the movement of whales. Movement

from Lynn Canal may have resulted from direct competition

for the same resource at the same time, by depletion of the

resource below levels sufficient to support humpbacks or as a

result of noise or the presence of fishing vessels. Fishing

activity or overharvesting (depletion of resource) of other

species at other trophic levels may indirectly impact humpbacks

through the food web/chains. There are insufficient data to

prove or disprove such hypotheses at this time.

[Pg 21]

In summary, a best interpretation of the available data is

that uncontrolled increase of vessel traffic, particularly of

erratic charter/pleasure craft, may have adversely altered the

behavior of humpback whales in Glacier Bay and thus may be implicated

in their departure from the Bay the past two years. The causal

mechanism of this adverse reaction to increased vessel traffic

remains unknown. The effects of increasing vessel traffic

apparently are exacerbated by the narrow physical confines of

Glacier Bay. This analysis is not clear-cut, however, and may

be confounded, at least in 1979, by possible shifts in the

occurrence and availability of preferred prey species of humpback

whales.

[5] This summary is based on information presented at the

meeting and resulting discussions.

ADEQUACY OF EXISTING DATA

In the Background and Possible Cause and Effect sections it

was stated that insufficient data exist to indicate cause and effect

relationships. Data are not sufficient in many areas, e.g.:

| 1) | environmental baseline data (biological, chemical, and physical) are inadequate; | |

| 2) | data available (i.e., Juraszs') have not been analyzed fully; | |

| 3) | changes in human use of areas are not adequately quantified (e.g., for fishing, cruising, touring, pleasure boating); and | |

| 4) | data on the acoustic characteristics of Glacier Bay or the vessels occurring in the Bay are not available. |

MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH ACTIVITIES

TAKEN OR UNDER CONSIDERATION[6]

The National Park Service (NPS) is responsible for managing

and overseeing the use of Glacier Bay National Monument

in support of the objectives defined for the Service, when it

was established in 1916; an excerpt from the Act creating the

Service in 1916 states that the purpose of the Service is:

"To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic

objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the

enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such

means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of

future generations."

The intent in establishing the Monument is defined in the

Proclamations of 1925 and 1939, sections of which are excerpted

and presented below.

[Pg 22]

"Whereas, there are around Glacier Bay ... a number of tide-water

glaciers of the first rank in a magnificent setting

of lofty peaks, and more accessible to ordinary travel

than any similar regions of Alaska,

"And, Whereas, the region is said by the Ecological Society

of America to contain a great variety of forest covering

consisting of mature areas, bodies of youthful trees which

have become established since the retreat of the ice which

should be preserved in absolutely natural condition, and

great stretches now bare that will become forested in the

course of the next century,

"And, Whereas, this area presents a unique opportunity for

the scientific study of glacial behavior and of resulting

movements and development of flora and fauna and of certain

valuable relics of ancient interglacial forests." (Proclamation

establishing Glacier Bay National Monument,

February 26, 1925.)

"Whereas, it appears that certain public lands, part of

which are within the Tongass National Forest ... have

situated thereon glaciers and geologic features of

scientific interest; and

"Whereas, a portion of the aforesaid public lands ... are

necessary for the proper care, management, and protection

of the objects of scientific interest situated on the

lands...." (Proclamation of April 18, 1939, adding lands

to the Monument.)

The management plans developed by the National Park Service for

the Glacier Bay National Monument did not anticipate, and

apparently have not been adequate to deal with, the increased

visitor and vessel traffic and their use of the marine environment

in the 1970's. Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations,

under which the National Park Service operates, contains a

section requiring any commercial business conducted or operating

within the boundaries of Service area to have a permit issued

by the Service. The cruise ship industry companies have not

as yet been placed under a permit system. However, it is the

intent of the Service to establish a regular system in the

future. All other commercial ventures operating on lands and

waters of the Monument are under contract or permit. Fishing

vessel activity is unregulated although the take of

Pacific halibut, (Hippoglossus stenolepis) is regulated by

the International Pacific Halibut Commission, and the take of

salmon and other finfish and shellfish is regulated by the Alaska

Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). The need for additional

resource/use plans and regulatory programs is recognized by the

National Park Service.

[Pg 23]

The NPS funded field studies of humpback whales by the

Juraszs in 1976-1979, analysis of some of the Juraszs' data,

and Hale's and Rice's (of the NPS Alaska area office)

report, "The Glacier Bay Marine Ecosystem—A Conceptual,

Ecological Model" completed in April 1979.

The movement of humpback whales in 1978 from Glacier

Bay to surrounding waters and the suggestion by the Juraszs'

field observations, that there may be a cause and effect

relationship between vessel activity and the whales' movement,

led the NPS to restrict some vessel activities in the 1979

season, and to seek Endangered Species Act Section 7 consultations

with the National Marine Fisheries Service in August 1979. The

Section 7 consultations were not completed at the beginning of

the meeting. Based in part upon NMFS's recommendations, the

NPS will consider various future management alternatives.

Restrictions imposed in 1979 were temporary (emergency closure

authority under Title 36 C.F.R.). Any regulations imposed for

1980 cannot be under emergency closure authority (unless an

emergency does arise which was unforeseen in setting up

regulatory systems). Regulations which can be foreseen at this

time as being necessary would have to proceed through the

normal Federal Register publication process. Enforcement of all

Federal laws and regulations within Glacier Bay is considered

to be the responsibility of the NPS.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has overall

responsibility, under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972,

for the conservation and protection of all whales including

humpback whales. The National Marine Fisheries Service in

cooperation with the Juraszs has conducted censuses of humpback

whales in southeast Alaskan waters in 1975 and 1976, used radio

tags to follow individual whales in Alaskan waters in 1976-78,

maintains a catalogue of humpback whale photographs and has

developed a computerized retrieval photo-identification system.

No research was conducted by NMFS in 1979. NMFS enforcement of

laws and regulations is conducted by a few people responsible

for large areas in southeast Alaska. A contract with the State

of Alaska until August 1, 1979, provided a broader presence of

enforcement personnel. That contract was not renewed. The

NMFS is now fully responsible for enforcement activities relating

to humpback whales except in areas such as Glacier Bay where the

responsibility is shared.

[6] This summary is based on information presented at the

meeting by National Park Service and National Marine Fisheries

Service Personnel.

ALTERNATIVE MANAGEMENT ACTIONS

Based on available information, vessel activity may have been

a factor contributing to the movement of whales from Glacier Bay

in 1978 and 1979. Alternatives available to manage vessel

traffic (assuming increased traffic has had or will have an

adverse effect on humpback whales) include:

[Pg 24]

1. Total closure of Glacier Bay to all vessels.

2. Closure to all vessels during the whale season.

3. Closure to all vessels during part of the whale season.

4. Total closure to all but certain classes of vessels—e.g.,

cruise vessels

charter vessels

fishing vessels

5. Seasonal closure to all but certain classes of vessels—e.g.,

cruise vessels

charter vessels

fishing vessels

6. Partial season closure to all but certain classes of vessels—e.g.

cruise vessels

charter vessels

fishing vessels

7. Alternatives 4, 5, or 6 with limitations on total

numbers of vessels of various classes given access

8. Alternatives 4, 5, 6 or 7 with restrictions applying

only to certain areas of the Bay

9. Establishment of a ceiling for all vessels or certain

classes of vessels during all or part of the whale

season

10. No restrictions on access but certain activities

prohibited or limited to certain areas or vessel

classes—e.g.: establish traffic lanes and permit

"deliberate" whale-watching only by a few trained

and licensed charter-boat operators.

11. No restrictions.

IDENTIFYING AND SELECTING THE MOST APPROPRIATE

RESEARCH/MANAGEMENT STRATEGY

Factors that should be considered in making research/management

decisions include (1) that the humpback whale is an

endangered species; (2) that there are statutory requirements

to protect the whales and their habitats; (3) that the cause

of the present problem is uncertain; (4) that the purpose of

the Monument is to provide for educational, recreational,

and scientific experiences; and (5) that limiting access or

restricting or closing the Monument to some or all vessel

activity could affect commercial and private enterprises,

including fishing.

[Pg 25]

Additionally, there are a number of types and possible

consequences of decision errors that should also be considered—e.g.,

| 1. | If Glacier Bay is a critical habitat, and if the movement of humpbacks is in response to whale watching vessels, pleasure boats, cruise vessels, etc., and if the movement is or will be irreversible; then the humpback whale population will be adversely impacted (e.g., carrying capacity reduced) if no action is taken. |

| 2. | If Glacier Bay is not a critical habitat, and if movement is due to whale watching vessels, etc., and it is or will be irreversible; then only the quality of visitor experience/value of monument is decreased if no action is taken. The impact on the population of humpbacks is not critical so long as suitable habitat is available elsewhere. However, the NPS mandate established in the 1916 Act still would not be fulfilled. |

| 3. | If all, or a specific type of, vessel traffic is prohibited or regulated, and the movement from the Bay is not caused, directly or indirectly by such traffic; then there will be decreased opportunity for human activity within the Bay, and increased economic impacts on fishermen and commercial operators that may have been unnecessarily restricted. |

The optimal short-term research/management strategy would

minimize the risks associated with the kinds of errors

discussed above, and include actions such as the following:

| 1) | by early 1980, compile and complete the analysis and evaluation of all existing and relevant data; | ||||||||

| 2) | based upon the evaluation of the best available data, promulgate temporary (one season) whale watching regulations and/or restrict access by all or certain classes of vessels or the number, frequency, or duration of visits of all or certain classes of vessels to certain areas at certain times of the year, as may be appropriate; | ||||||||

| 3) | continue and, if appropriate expand, surveys of whale/vessel numbers, distribution, movements, behavior and interactions in and outside Glacier Bay; | ||||||||

| 4) | identify and initiate additional research that is needed to identify and mitigate the cause or causes of the observed humpback whale movement from the Bay, e.g., | ||||||||

[Pg 26] |

|

The optimal long-range research/management strategy would

include:

| 1) | the development and implementation of a humpback whale recovery plan to include humpback whales in all of Glacier Bay, all of southeast Alaska and the North Pacific in general, including: the identification, designation and protection of critical humpback whale habitat; |

| 2) | the development of a universal and/or site-specific definition of "harassment" to apply to humpback whales in Glacier Bay, southeast Alaska and the North Pacific in general; |

| 3) | the development and implementation of a long-range research/management plan for the Monument including whale and environmental monitoring; |

| 4) | a determination as to the direct and indirect effects of incidental take, whale watching, fishing activity, etc. on humpback whales in Glacier Bay, Southeast Alaska and the North Pacific in general; and |

| 5) | a determination as to the long-term cumulative impacts of the degradation and destruction of habitat on the survival of the humpback whale throughout its range in the North Pacific. |

AGENCY RESPONSIBILITIES AND NEED FOR COOPERATION AND COORDINATION

There are many individuals, groups and organizations

interested or involved in finding solutions to problems

associated with humpback whales and human activities in

Glacier Bay. The need for management planning and research

[Pg 27]

programs has been identified. The identification of interested

and responsible organizations is necessary so that cooperative,

coordinated planning and research can occur. Hopefully, by

developing such plans or projects, minimum resources will be

expended to obtain satisfactory solutions. In addition, by

involving all interested and responsible individuals, groups,

or organizations at an early stage, cooperative efforts can

be maximized and disagreements identified and minimized.

The prime responsibilities of the National Marine Fisheries

Service and the National Park Service have been identified.

Other Federal agencies that should or might profitably be

involved include the Bureau of Land Management, the Office of

Coastal Zone Management, Sea Grant, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Coast Guard,

the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Army Corps of Engineers.

State agencies that should or might be profitably involved

include the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the State

Coastal Zone Management Commission, and the Alaska Department

of Natural Resources. Commercial and recreational companies

that organize fishing, tour, and charter activities, private

boaters, academic/scientific communities, and environmental

organizations are also important. Some of these organizations

have on-going, or plan to initiate, research projects, which may

provide data and information of importance to the problems

discussed in this report.

The Bureau of Land Management, New York Outer Continental

Shelf (OCS) Office, is presently initiating noise effects

studies on marine mammals. The U.S. Geological Survey at

Tacoma, Washington and Menlo Park, California is describing

and mapping marine sediment distribution, thickness and

characteristics within Glacier Bay. J. P. Mathews, of the

Institute of Marine Science, University of Alaska, is

summarizing the physical characteristics, especially water

mass characteristics and dynamics, of Glacier Bay. If

possible, these studies should be coordinated such that a

maximum amount of information can be obtained and used in

the management and research activities related to Glacier Bay

National Monument and the humpback whale.

SUMMARY

Humpback whales in the North Pacific are migratory,

spending the summer months in northern waters including

the inland waters of southeast Alaska. Records have been

maintained on the number of identifiable humpbacks seen in

these waters including Glacier Bay. In 1978, humpbacks

departed Glacier Bay after being "in residence" for a far

shorter time period than recorded previously; all but three

whales left the Bay within 24 hours of entering in 1979.

[Pg 28]

There has been an increase in vessel traffic and

activity within Glacier Bay during the 1970's. Such activity

may have been a factor in the movement of humpbacks from

Glacier Bay. Other factors which may have been at least

contributing but for which no known information exists, or is

inadequate at best, include: natural environmental changes

(chemical, physical, biological) or natural changes in the

movement of the whales.

Present management and research plans and activities

did not anticipate and, therefore, are inadequate to deal

effectively with present day problems associated with a rapidly

growing influx of people and vessels/aircraft into any

environment with limited space and resources. Some human

activities and the activities and behavioral patterns of

humpback whales may be mutually exclusive.

The most apparent important short-term research need is

to analyze and evaluate all available data, in order to

develop short and long term management plans and research

programs.

[Pg 29]

REFERENCES

Hale, L. Z. and R. G. Wright, 1979. The Glacier Bay

Marine Ecosystem. A Conceptual Ecological Model.

U.S. Department of the Interior, NPS, Anchorage

Office. 177 pp.

Jurasz, C.M. and V. Jurasz. 1979. Ecology of Humpback Whales.

Draft final report to the National Park Service.

[Pg 30]

APPENDIX A

AGENDA

Meeting to Review Information and Actions Concerning Humpback Whales in Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska

12-13 October 1979

Room 208, College of Fisheries

University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

12 October 1979

| 9:00 | Discussion of meeting objectives, agenda, and procedures (Dr. Robert Hofman, Marine Mammal Commission) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9:15 | Overview of available information on the distribution, abundance, and habitat requirements of humpback whales in the North Pacific (presentation by Dr. Michael Tillman, National Marine Fisheries Service) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9:30 | Physical/chemical characterization and history of Glacier Bay (presentation by Mr. Gregory Streveler, Glacier Bay National Monument) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10:00 | Review of available information concerning the past and present utilization of Glacier Bay by humpback whales (presentation by Mr. Charles Jurasz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10:30 | Coffee Break | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10:45 | Review of information concerning the past and present human use and its possible effects on Glacier Bay (presentation by Mr. John Chapman) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11:15 | Possible reasons for observed changes in utilization of Glacier Bay by humpback whales (discussion led by Dr. Robert Hofman) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12:15 | Lunch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

[Pg 31]

12 October 1979 (Continued)

| 1:30 | Review of on-going and planned research and management activities in Glacier Bay and contiguous waters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2:15 | Identification of additional research/management actions, if any, needed to protect humpback whales in Glacier Bay, e.g.: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4:30 | As possible, summarize and rank research and management activities not included in on-going or planned activities. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5:00 | Adjourn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

13 October 1979

| 9:00 | Continue discussion on ranking research and management activities not included in on-going or planned activities | |

| 10:00 | Coffee Break | |

| 10:15 | As possible, identify target initiation dates, target completion dates, optimal methods, time, money, personnel, logistic support, and equipment needed to initiate and complete ranked research and management projects | |

| 11:45 | Closing Remarks | |

| 12:00 | Adjourn |

[Pg 32]

APPENDIX B

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS AT MEETING TO REVIEW

INFORMATION AND ACTIONS CONCERNING HUMPBACK WHALES

IN GLACIER BAY NATIONAL MONUMENT

Mr. James A. Blaisdell

National Park Service

Fourth & Pike Building, Room 601

Seattle, Washington 98101

206/442-1355

FTS: 399-1355

Mr. Rob Bosworth

Institution for Marine Studies—HA-35

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington 98105

206/543-7004

Mr. John F. Chapman

Superintendent

Glacier Bay National Monument

P.O. Box 1089

Juneau, Alaska 99802

907/586-7137

Dr. William C. Cummings

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Marine Physical Laboratory (A005)

La Jolla, California 92093

714/452-2852

and

Oceanographic Consultants

5948 Eton Court

San Diego, California 92122

714/453-3257

Dr. Frederick C. Dean

Professor of Wildlife Management

Cooperative Park Studies Unit

Room 210, Irving Building

University of Alaska

Fairbanks, Alaska 99701

907/479-7672

Dr. Donald R. Field

Regional Chief Scientist

National Park Service

Pacific Northwest Region

Fourth & Pike Building, Room 601

Seattle, Washington 98195

206/442-1355

FTS: 399-1355

[Pg 33]

Mr. Robert Giersdorf

President

Glacier Bay Lodge, Inc.

Park Place Building, Suite 312

Seattle, Washington 98101

206/624-8551

Dr. Louis Herman

University of Hawaii, Kewalo Basin

Marine Mammal Laboratory

1129 Ala Moana

Honolulu, Hawaii 96814

808/537-2042

Mr. Larry Hobbs

Wildlife Biologist

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

National Fish and Wildlife Laboratory

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C. 20560

202/343-4516

Mr. Charles M. Jurasz

Ms. Virginia Jurasz

Sea Search

P.O. Box 93

Auke Bay, Alaska 99821

Mr. James W. Larson

Deputy Regional Chief Scientist

National Park Service

Alaska Area Office

540 W. 5th Avenue

Anchorage, Alaska 99501

907/271-4243

Mr. Paul A. Larson

Chief Resource Management and

Visitor Protection

National Park Service

Pacific Northwest Region

Fourth & Pike Building, Room 601

Seattle, Washington 98101

206/442-5670

FTS: 399-5670

Mr. William Lawton

National Marine Mammal Laboratory

NOAA/NMFS

7600 Sand Point Way, N.W., Building 32

Seattle, Washington 98115

206/442-5215

[Pg 34]

Dr. Jack W. Lentfer

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

210 Ferry Way

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907/586-6702

Dr. Katherine Ralls

Office of Zoological Research

National Zoo

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C. 20008

202/381-7315

Mr. Dale W. Rice

National Marine Mammal Laboratory

NOAA/NMFS

7600 Sand Point Way, N.E., Building 32

Seattle, Washington 98115

206/442-5004

Mr. G. P. Streveler

Research Biologist

Glacier Bay National Monument

Gustavus, Alaska 99826

907/697-3341

Mr. Steven L. Swartz

1592 Sunset Cliffs Boulevard

San Diego, California 92107

714/222-9978

Dr. Michael F. Tillman, Director

National Marine Mammal Laboratory

NOAA/NMFS

7600 Sand Point Way, N.E., Building 32

Seattle, Washington 98115

206/442-4712

FTS: 399-4711

Mr. Douglas G. Warnock

Deputy Director Alaska Area

National Park Service

540 West 5th Avenue, Room 202

Anchorage, Alaska 99501

907/271-4243

Mr. Roland H. Wauer

Chief, Division of Natural Resources

National Park Service

1100 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20240

202/523-5127

[Pg 35]

Dr. A. R. Weisbrod

Endangered Species Coordinator

National Park Service

1100 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20240

202/523-5127

Mr. Allen A. Wolman

National Marine Mammal Laboratory

NOAA/NMFS

7600 Sand Point Way, N.E., Building 32

Seattle, Washington 98115

206/442-4583

Mr. Milsted C. Zahn

Enforcement Division

Alaska Regional Office

National Marine Fisheries Service

Box 1668

Juneau, Alaska 99802

907/586-7228

[Pg 36]

APPENDIX C

| Data/Information and Research Needs Relative to Humpback Whales in Glacier Bay and Elsewhere (these lists are examples and not necessarily all inclusive). | |||||||||||||

| A. | Compilation and analyses of existing data (available data presently are not in a form that is optimally useful) | ||||||||||||

| I. | Whales | ||||||||||||

| a. | whale distribution and abundance in Glacier Bay and surrounding areas—by year, season, time of day, age, sex, weather (tide, rain, etc.), birds, boats (by total and by class), depth of water, distance from shore, prey species, effort,—— | ||||||||||||

| b. | movements/habitat use patterns—home range, temporal/spatial distribution of sightings of individually recognizable animals—are there resident, migratory and/or transient animals in the Bay or surrounding waters—do individuals have seasonal, annual cycles as to when/where they occur | ||||||||||||

| c. | undisturbed ("normal"—baseline) whale behavior—by age, sex, group size, group composition, time of day, season, location (descriptive and quantitative) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 4. interaction with other whales/social organization of whales | |||||||||||||

| d. | disturbed whale behavior—stimulus/response— behavior (as above) before, during and after an event—response distance (by age, sex, pre-event activity, location, time between events, time of day, season, weather, etc.)—recovery time (by age, sex, etc.). | ||||||||||||

| [Pg 37] | II. | Boat and Aircraft Traffic | |||||||||||

| a. | distribution and abundance in Glacier Bay and surrounding areas—by type (class), year, season, time of day, weather | ||||||||||||

| b. | movements/use patterns—by type, year, etc. | ||||||||||||

| c. | activities (behavior)—by type, year, etc. 1. whale watching 2. fishing (sport/commercial) | ||||||||||||

| III. | Habitat (physical, chemical, biological environment—by year, season, etc.) | ||||||||||||

| a. | physical—water temperature, sediment load | ||||||||||||

| b. | chemical—salinity, oxygen content, inorganic nutrient, pollutants | ||||||||||||

| c. | biological

| ||||||||||||

| B. | Improve base line data | ||||||||||||

| I. | Acoustic | ||||||||||||

| a. | ambient noise levels—representative areas (in and outside Bay), seasons, time of day, weather and tide conditions, sea state | ||||||||||||

| b. | boat- and plane-related noise—representative types, representative areas (in and outside Bay), speed (prop rpm), season, time of day, sea state | ||||||||||||

| II. | Whales—in and outside the Bay | ||||||||||||

| a. | abundance | ||||||||||||

| b. | distribution | ||||||||||||

| c. | movements (habitat use pattern)[Pg 38] | ||||||||||||

| d. | activity patterns | ||||||||||||

| e. | behavior vocalization | ||||||||||||

| f. | habitat requirement/areas of special significance | ||||||||||||

| III. | Boats and Planes—in and outside the Bay | ||||||||||||

| a. | abundance—by type, season, time of day | ||||||||||||

| b. | distribution— | ||||||||||||

| c. | movements— | ||||||||||||

| d. | activity in patterns | ||||||||||||

| IV. | Habitat | ||||||||||||

| a. | physical | ||||||||||||

| b. | chemical—pollutant levels | ||||||||||||

| c. | biological

| ||||||||||||

| C. | Experiments to validate hypothesis concerning possible effects of various stimuli on whales—representative stimuli, representative whales (age, sex), representative activities/behaviors (resting, feeding, traveling, vocalizing, etc.), representative areas, seasons, times of day, weather and environmental conditions. | ||||||||||||

| D. | Long-term monitoring (at regular intervals) | ||||||||||||

| I. | Environment (physical, chemical) | ||||||||||||

| II. | Whales (distribution, abundance, movements, activity patterns, vocalization patterns, cow/calf ratios) | ||||||||||||

| III. | Boat/Planes (abundance, type, distribution, movements, activities) | ||||||||||||

| IV. | Prey species | ||||||||||||

| V. | Fish catch | ||||||||||||

[Pg 39]

APPENDIX D

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE | |

| Washington, 20235 |

DEC 3 1979 F6:TRL

Mr. John Chapman

Superintendent

Glacier Bay National Monument

National Park Service

Box 1089

Juneau, Alaska 99802

Dear Mr. Chapman:

This letter responds to your August 4, 1979, request for consultation

pursuant to Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended,

relative to the population of the humpback whale in Glacier Bay, Alaska.

Your problem statement of the same date outlines the basic issue of human

activity in Glacier Bay National Monument that might be affecting humpback

whales. Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act requires that each federal

agency insure that its actions do not jeopardize the continued existence of

any listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of

critical habitat of such species. The consultation process requires our

comment and opinion on the problem.

Within this context, our response addresses those National Park Service

(NPS) actions controlling human activity that may, in turn, affect the

humpback whales within Glacier Bay.

In the North Pacific, the summer range of the humpback whale encompasses

the area from Bering Strait south to the Subarctic Boundary (ca. 40° N lat)

and extends in the east to about Point Conception, California, and the Sanriku

Coast of Honshu Island in the west. Humpbacks range into shallow coastal

waters more frequently than do most other balaenopterids and regularly occur

in sheltered inside waters of Prince William Sound and the Alexander

Archipelago of southeastern Alaska.

The wintering grounds of humpbacks in the North Pacific are centered in

three areas: (1) the coast and adjacent islands of west-central Mexico; (2)

the main Hawaiian Islands; and (3) the Bonin, Ryukyu, and Mariana Islands in

the western North Pacific. Some humpbacks that summer in southeastern Alaska

are known to migrate to both the Mexican and Hawaiian wintering grounds,

although others are found in southeastern Alaska during all months of the

year.

Prior to the rise of modern whaling in the late 1800's, the world

population of humpback whales exceeded 100,000, mostly in the Southern

Hemisphere. The North Pacific population probably numbered roughly 15,000 at

the turn of the century.

[Pg 40]

Whaling in southeastern Alaska began in 1907 with the establishment of

two land stations. The number of humpback whales at the start of this

earliest exploitation is unknown. Consistent catch records are available only

for 1912-1922, during which time 185 humpbacks were taken, with a peak catch

of 39 in 1916.

Since 1922, no whaling has been conducted in the territorial waters of

southeastern Alaska. However, the humpback whales of the inside waters were

exposed to additional exploitation as they migrated across the high seas or

through the coastal territorial waters of British Columbia, Washington,

California, and Baja California.

By 1966, when humpbacks were accorded complete legal protection by the

International Whaling Commission, the world population of the species had been

reduced to about 5,000. The North Pacific population now numbers about 1,000,

of which 600 or 700 winter in the Hawaiian Islands, and 200 or 300 winter in

Mexico. Only a few humpbacks have been sighted on the western North Pacific

wintering grounds in recent years. Since 1966 no trends in abundance have

been observed either for the North Pacific population as a whole or on any of

its wintering or summering grounds, including southeastern Alaska.

Based upon aerial and vessel surveys, the population that spends the

summer in the inside waters of southeastern Alaska numbers at least 70.

Photoidentification studies now underway tentatively reveal that the

population may exceed 100. Although it ranges throughout the area from Sumner

Strait northward, its main concentration areas are Frederick Sound-Stephens

Passage, where a minimum of 40 whales occurs, and Glacier Bay, where 20-25

whales occur. Humpback whales congregate in these areas to feed upon the

summer blooms of euphausiids, herring, and capelin. Some whales arrive in

June and stay on through early September, although as mentioned earlier, other

animals appear to remain through the winter months.

When humpback whales historically began occupying Glacier Bay is unknown,

but they have occurred there every summer over the past seven years of

investigation. Photoidentification techniques indicate that certain

individuals repeatedly return to feed there.

The availability of these and other feeding areas in southeastern Alaska

has not been constant over the years. Although Glacier Bay has lately been a

prominent feeding area, this was not always so since the area was covered by

an ice sheet during the 18th century; at that time the humpback population was

presumably at its maximum pre-exploitation level. There is some indication

that a seasonal feeding area in Lynn Canal was avoided by humpbacks coincident

with the onset of a herring fishery in 1972. With the cessation of that

fishery, humpbacks reoccupied the area in 1979. The possibility cannot be

discarded that these events are related.

The NPS records indicate that during 1976 and 1977, 20-24 individual

humpback whales moved into Glacier Bay during June and remained there into

August. In 1978 this pattern of use changed when most of the animals departed

[Pg 41]

by mid-July. In 1979 this use was modified further with fewer whales entering

the Bay and very few of those remaining in the Bay. Observations prior to

1976 are more general in nature, rather than numerical counts of record.

Human use of the Bay is reflected in NPS records, to wit:

| Year | Visitor Days | Large Ships | Private Boats | Fishing Vessels | ||||

| 1965 | 1,800 | |||||||

| 1969 | 16,000 | 115 | ||||||

| 1970 | 30,000 | 165 | ||||||

| 1975 | 72,000 | 113 | 353 | 824 | ||||

| 1976 | 85,000 | 123 | 318 | 656 | ||||

| 1977 | 120,000 | 142 | 534 | 523 | ||||

| 1978 | 109,000 | 123 | 699 | 458 | ||||

Most visitor use is via water access, with cruise ship and recreational

craft visitation levels increasing rapidly in recent years.

The recent NPS study indicates that increasing vessel traffic in Glacier

Bay may be implicated in the apparent departure of whales from Glacier Bay in

1978 and 1979. Data on the number of observed whale-vessel interactions in

Glacier Bay enables calculation of the following "interaction" index (data for

1979 not available):

| Year | Whale-vessel Interactions | Hours Observed | Index (interactions/hour) | |||

| 1976 | 98 | 261.1 | 0.38 | |||

| 1977 | 201 | 407.1 | 0.49 | |||

| 1978 | 268 | 397.5 | 0.67 |

Thus the occurrence of whale-vessel interactions increased 29 percent and

76 percent respectively in 1977 and 1978 over the 1976 base level. Despite

mitigative regulations in 1979, observers noted that whale-vessel interactions

continued at substantial frequencies.

The NPS data indicate that behavior of the humpback whales in Glacier Bay

changed significantly in 1978. Comparison of the frequency distributions of

behavioral responses indicates that, whereas distributions were the same in

1976 and 1977, both years were statistically different from 1978. In 1978,

more avoidance behavior occurred than in previous years, suggesting that the

whales reacted to the increased level of vessel traffic in 1978. However, the

causal mechanism for these reactions (whether it be increased noise or visual

stimuli) remains unknown.

All classes of vessels were not implicated equally in the increased level

of interactions which occurred in 1978. Cruise ship visitations actually

decreased 14 percent in 1978 from the 1977 high, while charter/pleasure craft

visitations increased 120 percent between 1976 and 1978. Commercial fishing

vessel traffic decreased 30 percent between 1976 and 1978. Charter/pleasure

craft were often observed to change direction and travel toward whales for a

closer look. Cruise ships and commercial fishing vessels, on the other hand,

[Pg 42]

neither paused for nor actively followed whales. Thus the most likely source

for increased interaction would appear to be the increased visitations by

charter/pleasure craft in 1978.

This conclusion seems to agree with the perceptions of scientists

examining other similar situations. The workshop on problems related to

Hawaiian humpback whales, sponsored by the Marine Mammal Commission in 1977,

concluded that vessel traffic not oriented toward whales did not ordinarily

seem to disturb them. Indeed, it was concluded that whales seem readily to

habituate to constant or familiar noises such as those produced by ships of

passage. A recent review on the possible effects of noises emanating from

offshore oil and gas development concluded that, unlike the abrupt response to

sudden disturbances, most whales become habituated to low-level background

noises such as would be associated with ship traffic (Geraci, J. R., and

D. J. St. Aubin, "Possible Effects of Offshore Oil and Gas Development on

Marine Mammals," prepared for the Marine Mammal Commission, August 1979.)

Moreover, it was noted that such behavior forms the underlying basis for the

success of whale watching cruises. Thus the erratic actions of

charter/pleasure craft rather than the more constant action of cruise ships

may be the major factor in possible harassment by vessels within Glacier Bay.

Cruise ships also may be implicated as potential sources of disturbance

due to the physical setting within Glacier Bay. A direct analogy may be seen

in the lagoons of Baja California where gray whales calve. Heavy barge and

freighter traffic associated with the salt industry, as well as a dredge

operating continuously in the lagoon's mouth, apparently drove gray whales out

of Laguna Guerrero Negro between 1957 and 1967. The whales reinvaded in

substantial numbers when vessel traffic was eliminated. The continued high

use of Laguna Ojo de Liebre by gray whales suggests that the movement of salt

barges, beginning there in 1967, may not have been such a nuisance. However,

since Laguna Ojo de Liebre is a much larger area than Laguna Guerrero Negro

and has a much wider entrance, the whales there may simply have been able to

move and coexist next to the barges. Such luxury of space may not be

available to the humpback whales of Glacier Bay and, due to geological

configurations of its basin, vessel noise may be accentuated there. These

factors may account for the unexpected reaction of humpbacks to cruise ships

in Glacier Bay.

The apparent departure of humpback whales from Glacier Bay in 1978 and

1979 may also be due in part to a change in the availability of food.

Euphausiids have historically been the primary feed within Glacier Bay in

July-August, although little research has been done to compare yearly levels

of this feed or to determine what level is necessary to support the whales.

The only available information derives from vertical plankton tows by the

REGINA MARIS in August 1979, which indicated that fewer euphausiids (5

percent) occurred in Glacier Bay as compared to Frederick Sound-Stephens

Passage. The humpbacks may have found the Glacier Bay food levels to be too

low, particularly in the face of continued high vessel use, and simply

departed to search for better concentrations elsewhere.

A similar abandonment of a prime feeding area, the Grand Banks, was

observed for the Northwest Atlantic humpback population and was thought to be

associated with the overfishing of capelin stocks there. Consequently, the

[Pg 43]

occurrence and distribution of humpback whales may be generally dependent upon

the occurrence and availability of its desired prey species.

In a worst case analysis, Glacier Bay is a feeding ground, and its long-term

abandonment would not be conducive to the conservation of the humpback

whale. Up to 20 or 25 individual whales would relocate to other areas,

increasing competition for food there. In such case a greater expenditure of

energy might be required to obtain the same quantities of food than would be

required in Glacier Bay. An increased energy expenditure would tend to

decrease the likelihood of humpbacks successfully increasing their numbers,

since growth and the onset of sexual maturity would be delayed.

Our present interpretation of the available data is that uncontrolled

increase of vessel traffic, particularly of erratically traveling

charter/pleasure craft, probably has altered the behavior of humpback whales

in Glacier Bay and thus may be implicated in their departure from the Bay the

past two years. Our conclusion, then, is that continued increase in the

amount of vessel traffic, particularly charter/pleasure craft, in Glacier Bay

is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the humpback whale

population frequenting Southeast Alaska. The alteration in the distribution

of the whales in Southeast Alaska can be expected to appreciably reduce the

likelihood of the recovery of the North Pacific humpback population,

especially when viewed as an incremental aggravation of the problem of

humpback/human interaction in general.

Until research reveals the need for more specific action, if any, we

offer the following as reasonable and prudent alternatives that the NPS should

institute in Glacier Bay to avoid jeopardizing the continued existence of the

North Pacific population of humpback whales:

We recommend that total vessel use of the Bay be restricted to 1976

levels, at the very least, since that year preceeded the high point of visitor

use in Glacier Bay during 1977. Commercial use of the Bay is predicated on a

permit system that should offer good control and accountability of the tour

industry. The routing of large vessels is relatively easy to regulate.

Recreational craft present the greater challenge to management control. The

continuing increase in the amount of recreational traffic in the Bay lends

considerable urgency to establishing effective controls.

Collectively, regulations should address vessel routing and vessel

maneuvering. The NPS has already regulated these activities to some extent.

Specific routes should be published, but the system should be flexible enough

to accommodate changes of areas of concentrated feeding activity.

We further recommend curtailment of vessel operator discretion in

pursuing, or approaching, whales. General guidelines prohibiting the pursuit

or willful or persistent disturbance of whales through vessel maneuvering

probably would offer better enforceability and public compliance than would

detailed regulations based on specified distances. Vessel operator behavior

should receive a thorough public educational effort, possibly through an

informative notice to each vessel.

[Pg 44]

Finally, we recommend that monitoring of the humpback population and of

whale-vessel interactions be continued and that all current data be fully

analyzed. New research should also be undertaken (1) to characterize the food

and feeding behavior of humpback whales in Glacier Bay and other areas; (2) to

ascertain the acoustic characteristics of vessels within the Bay and in other

areas with the aim of identifying equipment and/or modes of operation which

are inimical to the whales; and (3) to compare behavioral responses of the

humpbacks to vessels in Glacier Bay with those observed in other areas of

southeastern Alaska.

The conclusions and recommendations stated herein constitute our

biological opinion, and we consider consultation on this matter to be at an

end. Should significant new information or factors not considered in this

opinion arise, however, either we or NPS are obligated to reinitiate

consultation.

| Sincerely yours, |

Terry L. Leitzell Assistant Administrator for Fisheries |

Transcriber's Notes

The text herein presented is essentially that in the original report. To preserve continuity, some text was moved to rejoin text which had been split by Figures or Tables. Footnotes were moved to the end of the section in which they occur. To help distinguish them from text body footnotes, Table footnotes were changed from numbers to lower alpha characters. Three typos were corrected (see below).

The original report appears to have been a typewritten document and

species names were underlined instead of italicized as is usually the

case. Some other text is centered in all caps, that text has been formatted as headers (e.g., bold and larger sized font).

Typographical Corrections

| Page 11 (TABLE 4.): | visable => visible |

| Page 25 (Item 1.): | move- => movement |

| Page 33 (3rd Item): | Wildlive => Wildlife |

Featured Books

I misteri del castello d'Udolfo, vol. 3 (Italian)

Ann Ward Radcliffe

ito in cuibalia ella trovavasi. Non aveva pure obliato di qualeimportanza fosse per lei la conservaz...

Unhappy Far-Off Things

Lord Dunsany

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

The Rivet in Grandfather's Neck: A Comedy of Limitations

James Branch Cabell

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

The Teeth of the Tiger

Maurice Leblanc

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

Bat Wing

Sax Rohmer

��S EXPERIMENT CONCLUDED CHAPTER XXXIV. THE CREEPING SICKNESS CHAPTER XXXV. AN AFTERWORD ...

Food of the Crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos Brehm, in South-central Kansas

Dwight R. Platt

ture. Kalmbach (1918, 1920, 1939) continued these studies byanalyzing stomach contents from various ...

A New Bat (Myotis) From Mexico

E. Raymond Hall